JavaScript is one really versatile and platform agnostic language. You can build anything you want with it. Admittedly, some things are easier than others. I enjoy finding some non-standard projects I could dive into, just for the fun of it.

I often listen to a couple of online radio stations that I follow. I started wandering how difficult would it be to implement my own radio server. Well, I stopped thinking and decided to take some action. In this blog post I will show you what I've built.

This article was first published on the Logrocket blog. It was moved here when I started my own blog.

What we are building today

The goal is to implement a Node.js http server that will have an endpoint intended for streaming of the songs i.e. of the audio data. A client could then start consuming the data by making a request to that endpoint. We also need to implement some kind of a control panel, so we can manage what song will be streamed next. On top of that, we will implement a simple web page with a play button, similarly to how most of the online radios look.

We will put all of this into a single application, which would not be so smart for a real world solution. But hey, we are just having fun. The entire code from this article can be found on my GitHub repo here.

Let's begin!

Control panel

Since I love meddling with the terminal, and Node.js has a built in CLI, we will implement the control panel in form of a terminal GUI. After a little bit of research, I discovered that neo-blessed is a library made for this task. Neo-blessed has a concept of boxes. Those are basically windows that you can create, stylize and position in the terminal, similarly like components in a browser using HTML and CSS.

Let's first define the main screen that will wrap everything else. We will put it inside the View class:

class View {

constructor() {

const screen = NeoBlessed.screen({ smartSCR: true });

screen.title = 'Node Radio Mini';

screen.key(['escape', 'C-c'], () => process.exit(0));

this._screen = screen;

}

appendBoxes(boxes) {

for (const box of boxes) {

this._screen.append(box);

}

}

render() {

this._screen.render();

}

}

Here we create a main screen of the view layer, with a render method that we will use periodically to render the entire view. We attach some keys (Ctrl+C, Esc) which we can press to terminate the app if wanted.

Next, we need to implement the sections of the view. Each section will be a neo-blessed box, like mentioned earlier. We will implement a basic class for this, which will be extended by other classes later:

class TerminalBox {

constructor(config) {

this.box = NeoBlessed.box(config);

}

}

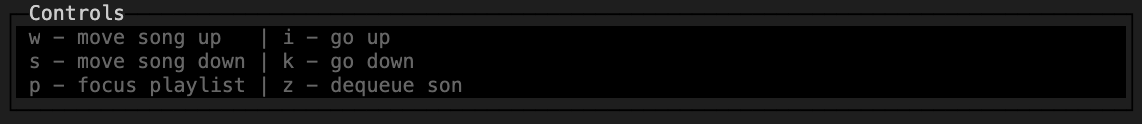

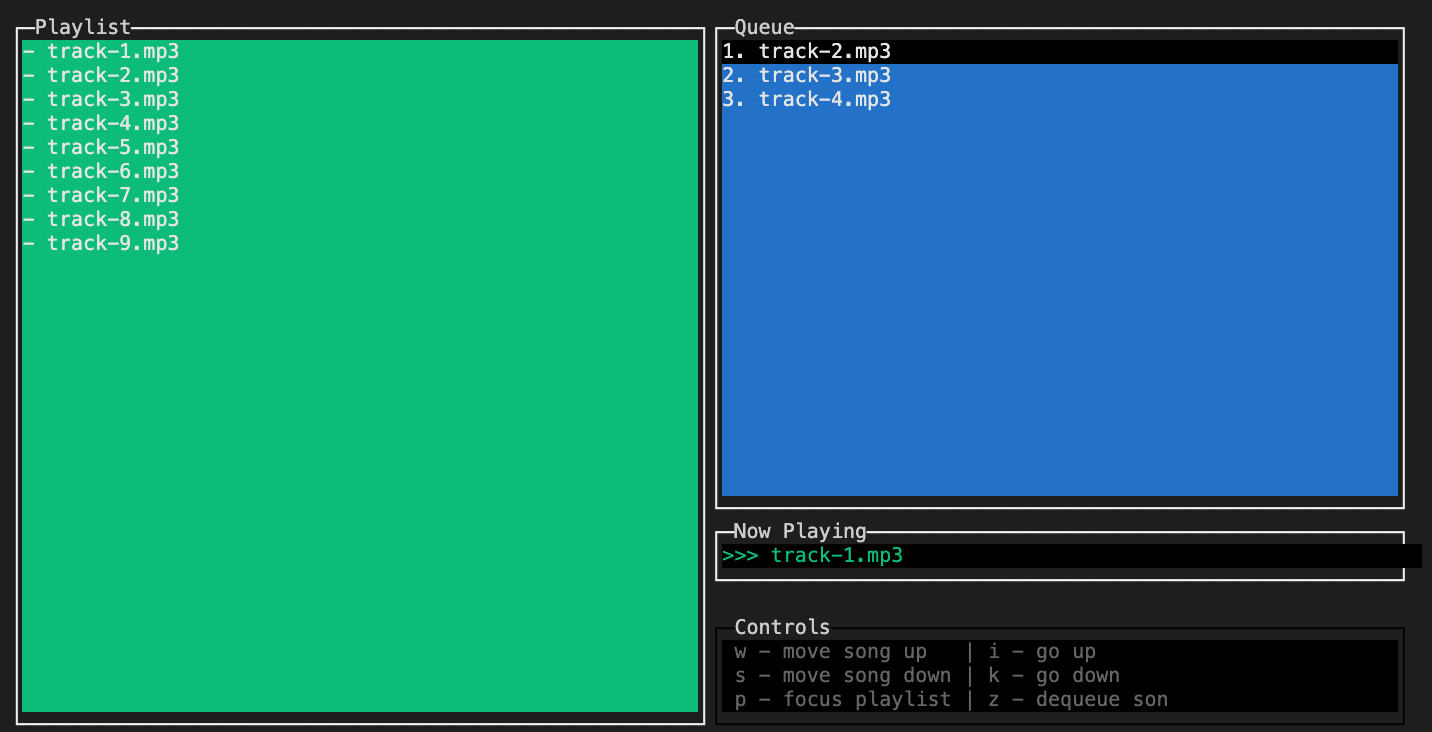

Four main sections (I will call them - boxes) are needed for a simple but convenient control panel. Those are:

- Playlist - list of all available songs

- Queue - list of queued up and ready to be played songs

- Now Playing - name of the song that is streaming at the moment

- Controls - keyboard keybindings instructions

Let's go with the simpler ones first. Controls box will contain hard-coded list of keyboard keybindings. Here's the code:

class Controls extends AbstractClasses.TerminalBox {

constructor(config) {

super(config);

this.setPlaylistTips();

}

setPlaylistTips() {

this.box.content =

`${keys.FOCUS_QUEUE} - focus queue | ${keys.SCROLL_UP} - go up\n` +

`${keys.QUEUE_ADD} - enqueue song | ${keys.SCROLL_DOWN} - go down\n`;

}

setQueueTips() {

this.box.content =

`${keys.MOVE_UP} - move song up | ${keys.SCROLL_UP}-go up\n` +

`${keys.MOVE_DOWN} - move song down | ${keys.SCROLL_DOWN}-go down\n` +

`${keys.FOCUS_PLAYLIST} - focus playlist | ${keys.QUEUE_REMOVE} - dequeue son`;

}

}

As I said, these boxes can be stylized according to our needs, and this is done on the instantiation of this class, by passing config options (line 3). Here are the configuration options for the Controls box:

{

"config": {

"label": "Controls",

"border": { "type": "line" },

"top": "85%",

"left": "50%",

"width": "50%",

"height": 5,

"style": {

"fg": "grey",

"bg": "black",

"border": {

"fg": "#000000"

}

}

}

}

All of the other boxes have similar configuration options, so I will not show them all. With the passed configuration options, the box will look like this:

Other three boxes will contain one or more child items. For that we need to make another extendable class similar like the first one (i.e. like the TerminalBox):

class _FocusIndexer {

constructor({ getIndexLimit }) {

this._index = 1;

this._getIndexLimit = getIndexLimit;

}

get() {

return this._index;

}

incr() {

if (this._index < this._getIndexLimit()) {

this._index++;

}

}

decr() {

if (this._index > 1) {

this._index--;

}

}

}

class TerminalItemBox extends TerminalBox {

constructor({ config, childConfig, bgBlur, bgFocus }) {

super(config);

this._childConfig = childConfig;

this._bgBlur = bgBlur;

this._bgFocus = bgFocus;

this._focusIndexer = new _FocusIndexer({

getIndexLimit: this._getNavigationLimit.bind(this),

});

}

_getHeight() {

// neo-blessed box has two invisible items prepended, so we need '-2'

return this.box.height - 2;

}

_getNavigationLimit() {

return Math.min(this.box.children.length - 1, this._getHeight());

}

_setActiveChildColor(color) {

const activeChild = this.box.children[this._focusIndexer.get()];

if (activeChild) {

activeChild.style.bg = color;

}

}

focus() {

this._setActiveChildColor(this._bgFocus);

this.box.focus();

}

blur() {

this._setActiveChildColor(this._bgBlur);

}

scroll(scrollKey) {

if (this.box.children.length === 1) {

return;

}

const unfocusedIndex = this._focusIndexer.get();

const unfocusedChild = this.box.children[unfocusedIndex];

unfocusedChild.style.bg = this._bgBlur;

if (scrollKey === keys.SCROLL_UP) {

this._focusIndexer.decr();

} else if (scrollKey === keys.SCROLL_DOWN) {

this._focusIndexer.incr();

}

const focusedIndex = this._focusIndexer.get();

const focusedChild = this.box.children[focusedIndex];

focusedChild.style.bg = this._bgFocus;

}

_createBoxChild() {

throw new Error('_createBoxChild() method not implemented');

}

createBoxChildAndAppend(content) {

const boxChild = this._createBoxChild(content);

this.box.append(boxChild);

}

}

The most important things to note here is that this class contains child items, which are also neo-blessed boxes. That's why in the constructor there are both config and childConfig props passed.

Also, the class has a scroll method by which you can navigate the items with the help of the illusion made by different coloring of blurred and focused items. To help keep track of the index of the focused child item, we are using a helper class called FocusIndexer (defined on line 1 and instantiated on line 27).

And lastly there is a createBoxChildAndAppend method for adding new children. This is not all but in the interest of time I will stop here.

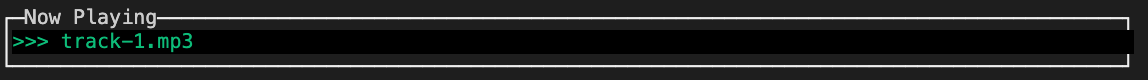

Now Playing box will have only one item, a song that is currently played, this is how we will implement it:

class NowPlaying extends AbstractClasses.TerminalItemBox {

_createBoxChild(content) {

return NeoBlessed.box({

...this._childConfig,

top: 0,

content: `>>> ${content}`,

});

}

}

When an instance is created and inserted into the main view, it will look like this:

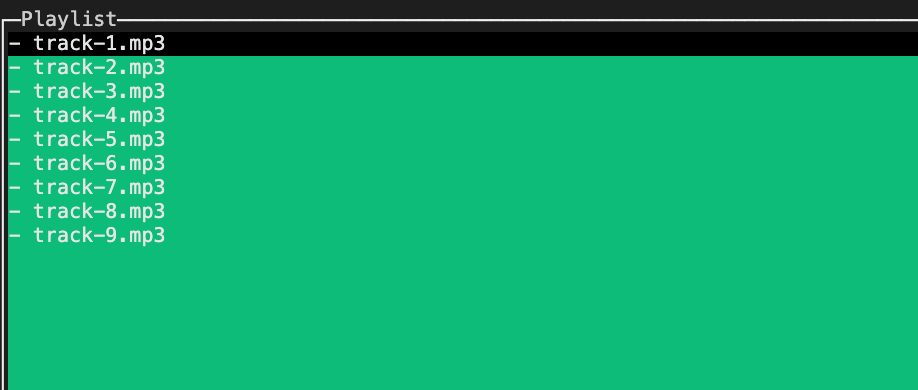

Playlist box will be used for storing the list of all the songs from the directory where the app has been run. Almost all important features for this are already implemented in the TerminalItemBox class, so we will extend it:

class Playlist extends AbstractClasses.TerminalItemBox {

/*

.....

*/

_circleChildrenUp() {

const temp = this.box.children[this.box.children.length - 1].content;

this.box.children.reduceRight((lowerChild, upperChild) => {

lowerChild.content = upperChild.content;

return upperChild;

});

this.box.children[1].content = temp;

}

_circleChildrenDown() {

const temp = this.box.children[1].content;

this.box.children.reduce((upperChild, lowerChild, index) => {

if (index > 1) {

upperChild.content = lowerChild.content;

}

return lowerChild;

});

this.box.children[this.box.children.length - 1].content = temp;

}

_circleList(key) {

if (this._focusIndexer.get() === 1 && key === keys.SCROLL_UP) {

this._circleChildrenUp();

} else if (

this._focusIndexer.get() === this._getHeight() &&

key === keys.SCROLL_DOWN

) {

this._circleChildrenDown();

}

}

/*

.....

*/

}

The one important thing this is worth mentioning here is that this class implements the circleList method, which is used for enabling navigating the child items even if they overflow the terminal viewport.

This is how the playlist will look:

Queue is the last box we need to implement. Similar to the Playlist it will extend the TerminalItemBox class. But this is where the similarities end. This class will not only be in charge of the view layer which visually represents all the songs queued up for streaming, but it will also contain all the functionalities for the streaming and piping data to all the consumers (i.e. clients). We will cover that in detail in the next section. For now, here is the implementation, at least the part for the view layer:

class Queue extends AbstractClasses.TerminalItemBox {

/*

.....

*/

_changeOrderInBoxChildren(key) {

const index1 = this._focusIndexer.get();

const child1 = this.box.children[index1];

child1.style.bg = this._bgBlur;

if (key === keys.MOVE_UP) {

this._focusIndexer.decr();

} else if (key === keys.MOVE_DOWN) {

this._focusIndexer.incr();

}

const index2 = this._focusIndexer.get();

const child2 = this.box.children[index2];

child2.style.bg = this._bgFocus;

[child1.content, child2.content] = [

`${getFirstWord(child1.content)} ${discardFirstWord(child2.content)}`,

`${getFirstWord(child2.content)} ${discardFirstWord(child1.content)}`,

];

return { index1, index2 };

}

}

Only thing worth noting here is the Queue box’s changeOrderInBoxChildren method. This method allows the user to move the songs up or down in the queue.

Finally, we have the whole view layer ready. Here is the result:

After we instantiate instances of the four classes (i.e. boxes) which are playlist, queue, nowPlaying and controls, and the main view component that was mentioned at the beginning, we need to attach listeners for the keyboard keypress events, so we can enable a user to make actions on the control panel. Here is a part of that code:

const _addPlaylistAndQueueListeners = () => {

const playlistOnScroll = (scrollKey) => {

playlist.scroll(scrollKey);

view.render();

};

playlist.box.key(keys.SCROLL_UP, playlistOnScroll);

playlist.box.key(keys.SCROLL_DOWN, playlistOnScroll);

playlist.box.key(keys.QUEUE_ADD, () => {

const focusedSong = playlist.getFocusedSong();

const formattedSong = Utils.discardFirstWord(focusedSong);

queue.createAndAppendToQueue(formattedSong);

view.render();

});

playlist.box.key(keys.FOCUS_QUEUE, () => {

playlist.blur();

queue.focus();

controls.setQueueTips();

view.render();

});

/*

......

*/

};

playlist.box.key(key, handler) is a method provided by neo-blessed by which you can set key listeners, which is nice and handy.

We have finished making the control panel. We can now, using the defined keyboard shortcuts, browse the songs in the playlist and send the songs we like to the queue.

Stream magic

The songs from the queue should be sent to every consumer that is listening at the moment. This is the next thing we need to implement. As I already mentioned, Queue class will be in charge of showing the queued up songs in the GUI. On top of that this class will contain the logic for emitting the songs to the clients.

Since we want to gradually broadcast audio data to the clients, it is somewhat obvious that this will need to be implemented via streams, or in our case - the Node.js Stream API.

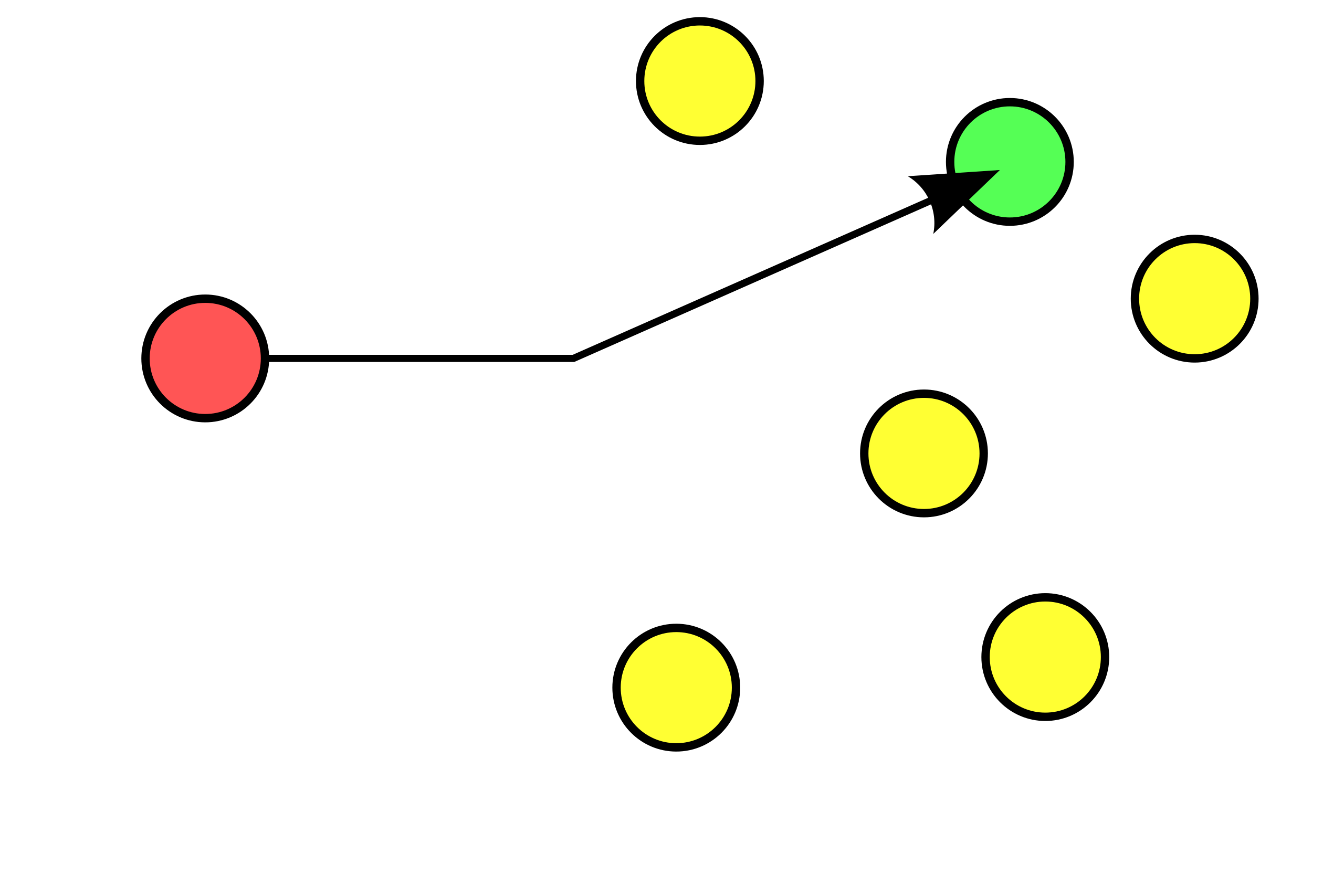

Now the first thing to note here is that the Stream API is primarily invented for a one-to-one (unicast) transfer of chunked data in a pull based manner, meaning that the consumer determines the speed of the transfer based on the speed by which it can process the data.

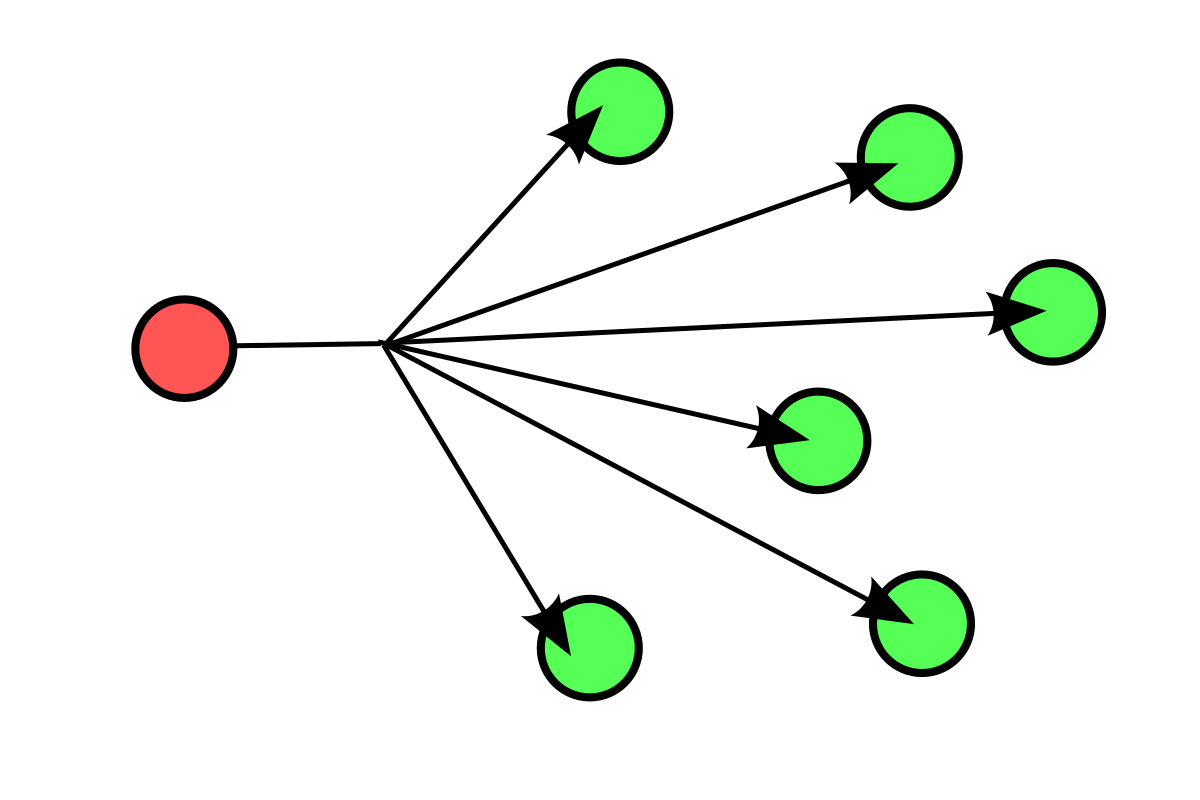

And we need to do quite the opposite here. We need to have a one-to-many (broadcast) transfer of data, and we need the producer to be in charge of the speed of the transfer in a push based manner (the reason for this is quite obvious - we want all of the consumers to receive approximately the same part of a song at a single point of time).

Just to mention here - in Node's Stream API terminology producer is a readable stream (stream.Readable class) and a consumer is a writable one (stream.Writable class). Of course, one entity can be both a readable and a writable at the same time (stream.Transform class).

The most popular way of consuming a readable stream (i.e. a producer), amongst many existing, is by using the *.pipe()* method:

/*

producer.pipe(consumer);

*/

readable.pipe(writable);

Having said all of the above, this method is not going to serve our needs, since it is meant for a one-to-one transfer and the speed of the streaming is determined by the writable. So we can't just have one readable stream and pipe it multiple times, like this:

// won't work

readable.pipe(writable1);

readable.pipe(writable2);

readable.pipe(writable3);

It won't work because the readable stream can be consumed only once, and with the .*pipe()* method the first attached writable will be in charge of the consuming. Now in this example the other writables would receive some or even all of the streaming chunks, but it isn't guaranteed by this api. Another con is that you cannot stream at all unless you have a writable (i.e. a consumer) present. Since you have to pipe the readable somewhere.

But no problem, there is a different strategy we can use here. Another way to consume a readable stream is by listening the data event. In the handler for that event we can manually write the streamed chunk to all the writables, which would look like this:

const writables = [writable1, writable2, writable3];

readable.on('data', (chunk) => {

for (const writable of writables) {

writable.write(chunk);

}

);

This is much better. As soon as a handler is attached to the data event, the readable will go to the flowing mode and start streaming the data. We now have an elegant way to achieve one-to-many transfer, i.e. to send the same chunk of data to every registered writable. On top of that, if no writable is present, the readable will continue to stream the data, which is what we need since songs on pretty much every radio must continue playing even if no one is listening. :)

We still didn't solve all the problems. If we only attach the handler, like in the last code snippet, the readable (i.e. the song) would be consumed pretty much in a couple of seconds. We don't want that. We want to stream the data slowly. This can be done by using some kind of a throttling mechanism, to slow down the streaming of the chunks. In Node.js land we can implement that with a transform stream (which is both a readable and a writable, like already mentioned) and a timer function. The goal of this transform stream is to receive chunks from a readable, and output the chunks to a writable but only at a determined rate, which is going to be handled by a timer function inside the transform stream itself.

Since there are several published packages that already solve this problem, we're going to use one called 'throttle' from NPM. It is a class which you can use to instantiate a new transform stream by passing one argument, a number, representing bytes per second. This transform stream would then limit the streaming of the chunks to be no faster than the bytes per second you provided:

const Fs = require('fs');

const Throttle = require('throttle');

const readable = fs.createReadStream('/location/of/a/song.mp3');

const throttle = new Throttle(128000 / 8);

const writables = [writable1, writable2, writable3];

readable.pipe(throttle).on('data', (chunk) => {

for (const writable of writables) {

writable.write(chunk);

}

);

With this, the readable would not get consumed in mere seconds. The speed of the streaming would now be more close to how a song would be played in real time. But how to determine what is close to real time? And what is the number passed while creating a new instance of the Throttle class (on line 5)?

Here lies our last problem. Every audio file has a bitrate property, expressed in bits per second (bps). We need that number to determine at what speed to do the streaming. In the last code snippet I defaulted to 128000 bps (128 Kbps) since plenty of songs have that bitrate (in the snippet it is divided by 8, since the Throttle class received bytes per second instead of bits). But we don't want to default to a certain value and hope for the best. We must determine the bitrate for every song that we stream. Luckily, there's a way we can do that. We will use '@dropb/ffprobe' **package from NPM (this package requires '*ffmpeg*' binary installed on the operating system).

With the help of this package, we can determine the bitrate like this:

const Fs = require('fs');

const Throttle = require('throttle');

const { ffprobeSync } = require('@dropb/ffprobe');

const bitRate = ffprobeSync('/location/of/a/song.mp3').format.bit_rate;

const readable = fs.createReadStream('/location/of/a/song.mp3');

const throttle = new Throttle(bitRate / 8);

const writables = [writable1, writable2, writable3];

readable.pipe(throttle).on('data', (chunk) => {

for (const writable of writables) {

writable.write(chunk);

}

);

Finally! A solution that works properly!

If we implement the streaming logic like this, songs will be streamed at a speed that closely matches the playing speed. Of course, whatever we do, we cannot match the precision of pro radio servers like Shoutcast and Icecast. But, it is good enough for me. :)

Let's just put this stream logic inside our Queue class, like mentioned at the beginning of this section:

class Queue extends AbstractClasses.TerminalItemBox {

constructor(params) {

super(params);

this._sinks = []; // list of active sinks/writables

this._songs = []; // list of queued up songs

this._currentSong = null;

this.stream = new EventEmitter();

}

/*

......

*/

makeResponseSink() {

const responseSink = PassThrough();

this._sinks.push(responseSink);

return responseSink;

}

_broadcastToEverySink(chunk) {

for (const sink of this._sinks) {

sink.write(chunk);

}

}

_getBitRate(song) {

const bitRate = ffprobeSync(`${process.cwd()}/${song}`)).format.bit_rate;

return parseInt(bitRate);

}

_playLoop() {

this._currentSong = this._songs.length

? this.removeFromQueue({ fromTop: true })

: this._currentSong;

const bitRate = this._getBitRate(this._currentSong);

const songReadable = Fs.createReadStream(this._currentSong);

const throttleTransformable = new Throttle(bitRate / 8);

throttleTransformable

.on('data', (chunk) => this._broadcastToEverySink(chunk))

.on('end', () => this._playLoop());

songReadable.pipe(throttleTransformable);

}

startStreaming() {

this._playLoop();

}

// .....

}

We are storing queued up songs in the this._songs array. The songs can be added by navigating the playlist in the terminal GUI and using the keyboard shortcuts we defined in the first section of the article.

Consumers (i.e. writables), to which we must stream the data, will be stored in the this._sinks array, with the help of the this.makeResponseSink() method. I will cover more on how the consumers will be added in the next section.

Queued up songs will be streamed one by one, as we can see in the this.playLoop(), and if all of the songs are finished, we will repeat the last one. This way we make sure that the server will never stop streaming.

Server

Now, since we implemented the view layer and the streaming logic, the only thing we need to do is create a http server. We will use Hapi.js, although any server would do just fine.

We will implement a http endpoint which will do two things when a request comes:

- register the client as a consumer and add it to our queue's

this._sinksmap (line 6) - start streaming the data back to the client

In Hapi.js, route will look something like this:

server.route({

method: 'GET',

path: '/stream',

handler: (request, h) => {

const responseSink = queue.makeResponseSink();

return h.response(responseSink).type('audio/mpeg');

},

});

The server also needs to be able to serve static files, so we can provide a handy web page with some radio controls. Implementing that in Hapi.js is trivial and I will not show that here. But this is the simple page that will be served:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Node.js Radio</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" media="screen" href="/index.css" />

<script src="/index.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<div id="main">

<h1 id="title">Very Cool Radio</h1>

<img id="logo" src="/nodejs-logo.png" />

<div id="radio">

<audio

id="audio"

src="/stream"

preload="none"

controls

autoplay

></audio>

</div>

</div>

</body>

</html>

The audio element (line 13) will make a request to src="/stream" (which is the enpoint where the browser will automatically make a request to) when the page loads.

And here is our simple but nice web page:

Summary

Phew, this article ended up being longer than I expected. For you, avid readers, here is the summary of what we did here:

- we implemented a http server that will stream the audio data to all the clients

- we implemented a control panel in form of a terminal GUI, by which a person managing the server can browse the list of the available songs and queue them up to be streamed next

- we implemented a static web page containing the audio element which will start consuming the audio data from a server endpoint

Again, the entire repo for this article is located here, and it contains a fully-functioning app with some features that were not shown here.

This was a lot of fun. I had a great time and hope you did as well!